| |

Now let's look at how this applies to the heart.

The orientation of a heart is described relative to an imaginary line

drawn from the base of the heart (valve plane) to the apex. This

line normally goes right through the middle of the LV. Think of

the valve plane as the wings of an airplane and the apex as the tail and

the line drawn from the midpoint of the base to the apex as the axis of

the heart. In a coronal image the axis of the heart will have a

yaw around 30°-40° as measured from the horizontal (Figure

2). A tall, skinny person is likely to have a heart that hangs down

in his thoracic cavity; a more vertical orientation, with a yaw of greater

than 45°. A short, overweight person is likely to have a heart

that lies primarily in a left-right or horizontal orientation with a yaw

less than 25°. (A perfectly horizontal heart would have a yaw

of 0°)

|

|

|

|

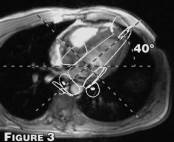

Once you have determined the yaw of the patient's heart,

you can easily acquire a long axis image through the LV. From this

you can determine the pitch angle or elevation of the apex above the valve

plane (figure 3). Typical values range from 25° to 50°.

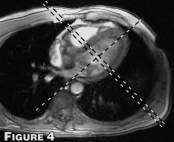

From this image it is a simple matter to obtain short axis images that are

perpendicular to the long axis of the LV. (Figure 4)

|

|

|

|

The long axis image obtained above is neither a 2-chamber nor

a 4-chamber view but something in between. In order to obtain a good

4-chamber view you need to know the roll angle of the heart. This

can be determined by looking at a short axis view just above the valve plane.

We define the roll angle as the angle a line draw from the middle of the

LV to the furthest corner of the RV makes with the horizontal plane.

(Figure 5) (Typical values range from 30° to 45°) An image

through this line will give a very good 4-chamber view. (Figure 6)

A 2-chamber view can be obtained using either the same short axis view as

used for the 4 chamber (Figure 5) or by using the 4 chamber view. (Figure

6) |

|

|

| One last item to deal with before we get to

the step-by-step instructions. Which sequence(s) should you use for

determining the imaging planes? Two requirements: 1) it has to be

fast and 2) the anatomy has to be just recognizable not necessarily great.

One possibility is a double IR FSE sequence which will provide one image

per breath hold. Decent solution because it gives good quality anatomy

but we prefer a sequence that gives at least one systolic and diastolic

image and/or multiple slices per breath hold. We have decided to

use a fast gradient echo with a large PEG size (20 to 24). This provides

2 to 4 cardiac phases in 4 to 8 heartbeats (depending upon patient heart

rate and phase sampling ratio which in turns depends upon the patient size,

FOV and imaging plane.) All of the images can be acquired with thick

slices 10-15 mm and large FOV 40 to 48 cm. |